Deciphering the Meaning of the Day of the Dead Altar in Mexico

Though 100+ photos, discover the meaning behind 28 objects commonly left at Day of the Dead altars in Jalisco, Mexico.

The Day of the Dead altar is at once mysterious and visually legible, a cultural touchstone whose multi-layered symbology can be decoded by a knowledgeable observer.

The holiday’s indigenous, millennia-old origin has been transformed and molded by centuries of Catholic and regional influence: it’s not celebrated exactly the same in any two regions. But there is a commonality which ties everything together, especially when it comes time to build the altar.

In this article with over 100 photos that I’ve taken over the past 10 years, you’ll learn about 28 kinds of objects that can be found on the Day of the Dead altar in Mexico.

- 1. The Entrance

- 2. Candles

- 3. Photos

- 4. Skulls

- 5. Marigolds

- 6. Dyed Sawdust Carpets

- 7. Incense

- 8. Salt

- 9. Catrinas

- 10. Papel Picado

- 11. Music

- 12. Pan de Muertos

- 13. Seeds and Grains

- 14. White Cross

- 15. Personal Belongings

- 16. Shoes

- 17. Clothes

- 18. Soap and Water

- 19. Mirrors

- 20. Petates

- 21. Plates of Food

- 22. Alcohol

- 23. Fruits and Vegetables

- 24. Sugarcane

- 25. Coronas

- 26. Metates and Molcajetes

- 27. La Lotería Mexicana

- 28. Traditional Dolls

What is a Day of the Dead Altar?

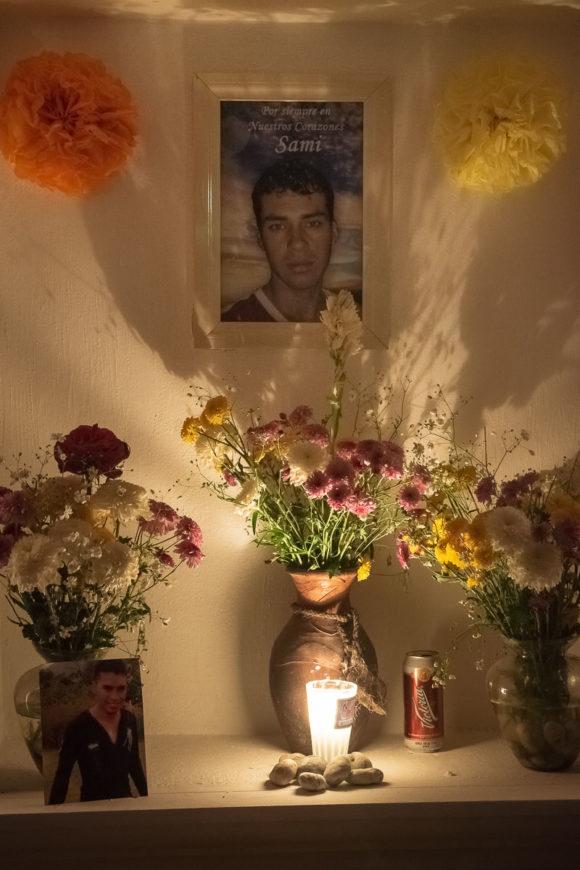

Day of the Dead altars are made as a way of remembering and honoring deceased friends and family. The altars help guide the spirits back to the land of the living on the Noche de Muertos on the night of November 2.

Incense, flowers, candles, clothes, and food are left out to lead the dead to the altar and their waiting families, who spend the night in the graveyard singing, playing music, eating, drinking, and remembering.

Altars are also made the day before November 2 for El Día de los Angelitos (the Day of the Little Angels).

Related Posts About The Day of the Dead

Video: Watch this short video slideshow of 25 objects left on the Day of the Dead altar in Jalisco, Mexico.

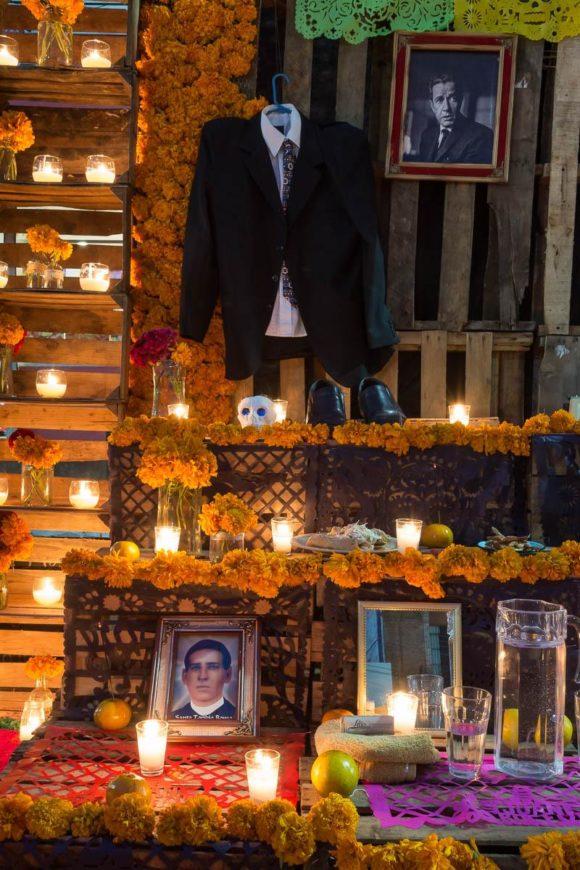

First, a Few Complete Day of the Dead Altars

The Entrance

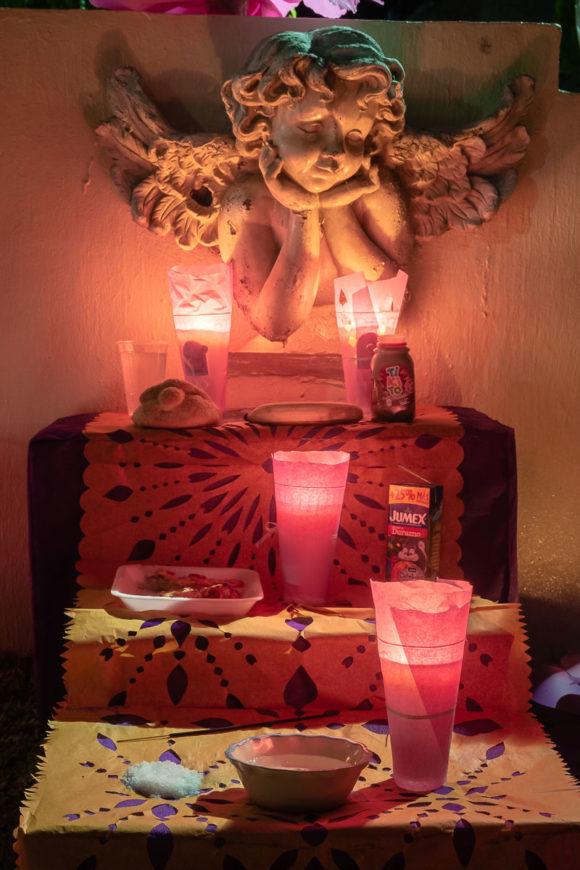

The Day of the Dead altar is usually built on multiple levels, with some extravagant, community-built versions reaching a story high. But the most common altars are divided into three sections: the ground-level entrance called la entrada, a mid-tier section with a table of offerings, and the highest level representing heaven, where photos of the dead are hung alongside images of favorite saints, the Virgin of Guadalupe and Jesus.

On November 2, the dead come back to visit the living, and the entrance of the altar (ofrenda or altar in Spanish) is built to welcome and guide them to their altars. Common elements are laid along the entrance, such as candles, skull decorations, seeds, a carpet of colorful sawdust, incense, and marigolds.

Candles

Once everything on the altar is in place and darkness is at hand, everyone begins lighting up the candles. As twilight fades away, and family and friends gather around, the flickering lights begin to fill the nooks and recesses of the displays with a warm glow, which helps guide the dead to their altar.

Photographs of the Departed

Skulls

Placed alongside photos and possessions of the dead, the graphic and macabre representation of the human skull, free of its skin and facial features, stripped by decay to its common bony element, confronts the observer with her own mortality. One night years from now, her spirit will return to this family spot to be honored and remembered, too.

The dark, hollow eyes of the skulls peer out from comforting glow of the altar, otherwise contrasting against the night’s overwhelmingly jovial atmosphere, which can reach the order of whimsy and humor, and at times might seem to border even on irreverence.

Marigolds

The brightly colored orange petals of the marigold are said to represent the sun. Along with its sweet, floral scents, which get carried along by the evening winds, the flowers lead the spirits to their shining altars.

Parts of the Day of the Dead altar are still relatively new additions to the centuries-old tradition. But aspects such as the marigold have found a vital place at the altar, going back to the holiday’s indigenous origins.

Their blooms are used to line graves and adorn altars, sometimes laid down to create a physical path for the dead to follow to their offerings.

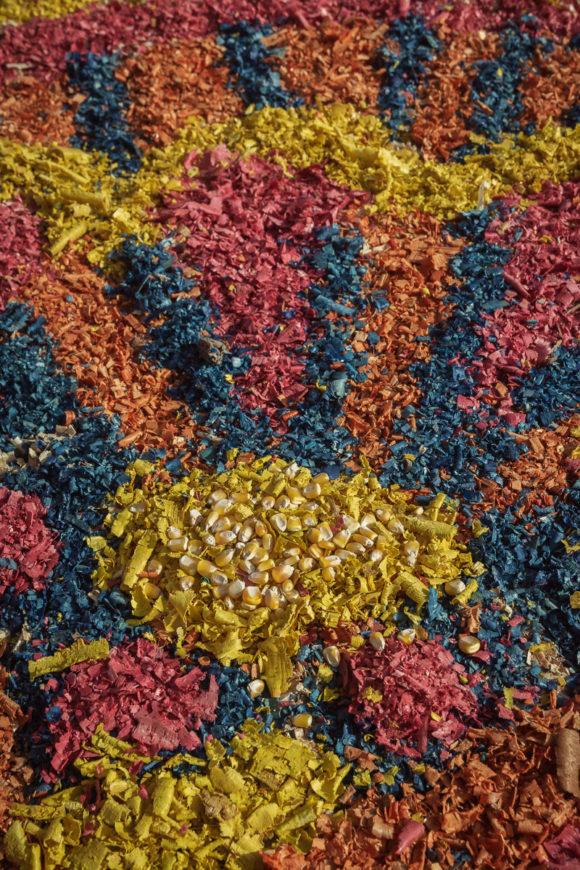

Dyed Sawdust Carpets

Elaborate, hand-designed patterns of colorful sawdust will sometimes line the entryway of the altar, serving as a path for the dead. These colorful, patterned carpets of dyed wood shavings called tapetes de aserrín (sawdust carpets) can span the length of a block in some elaborate cases, and take a dedicated team of a dozen or more people the afternoon to create.

The tradition arrived in the New World with the Spanish conquistadors, and today is still upheld in Mexico and Central America, especially for the Day of the Dead celebrations in Central Mexico.

Learn more about how tapetes are constructed for the Day of the Dead.

Incense

Salt

Salt acts to cleanse the spirits and purify their souls during the following year.

Catrinas

La Catrina has been an essential element of the Day of the Dead ever since printmaker José Guadalupe Posada made his etching La Calavera Catrina in 1910. His image of an elegantly dressed catrina is not only an iconic part of the Day of the Dead, but also recognized worldwide as an emblematic symbol of Mexico. If you like the catrinas, you might enjoy this series of photos of catrinas on the Day of the Dead.

The “Day” of the Dead really spans three days and nights, starting October 31. This altar had been decorated for Children’s Day, which takes place November 1. It’s said the children are eager to run back to their families, so they arrive the night before the adults do on November 2.

Papel Picado

These perforated designs are sometimes made from plastic, but the traditional ones are still hand-cut in tissue paper, making it a recognized Mexican folk art.

Music

Musicians will wander the graveyard November 2 and families can hire them while everyone is gathered around the tomb celebrating. Sometimes a radio might play the favorite songs of the dead.

Pan de Muertos

This type of sweet bread is only sold in the weeks leading up to the Día de Muertos. It’s eaten by the living, as well as left as an offering on the altar for the returning dead. Pan de muertos is one of the most important elements of an ofrenda, with a long history extending to prehispanic times.

Aztecs, during their sacrifice rituals, would cut the still-beating heart from the chests of the sacrificed. The Spanish, of course, aimed to put a stop to this non-Christian behavior when they arrived to conquer Mexico at the beginning of the 16th century. They forced the substitution of bread for the heart, shaped in the form of a corazón and painted in a glaze of red sugar.

This is the origin of today’s pan de muertos, which has regional variants across Mexico. The Spanish, of course, aimed to put a stop to this non-Christian behavior when they arrived to conquer Mexico at the beginning of the 16th century. They forced the substitution of bread for the heart, shaped in the form of a corazón and painted in a glaze of red sugar. This is the origin of today’s pan de muertos, which has regional variants across Mexico.

José Luis Curiel Monteagudo, in his book Azucarados Afanes, Dulces y Panes, says, “To eat pan de muertos is for the Mexican a true pleasure, considering the cannibalism of bread and sugar. The phenomena is treated with respect and irony. Defying death, they make fun of her by eating it.”

Seeds and Grains

Representing the element of earth, seeds or grains are left out in bowls or combined with the dyed sawdust to create designs on the floor of the altar’s entrance.

White Cross

A white cross today comes from Christianity but originates as a way to signify the four cardinal directions of north, south, east and west. The altar has evolved through the centuries, as the Catholic overseers of post-conquest Mexico incorporated indigenous ideas into its Allhallowtide triduum. Sometimes other colors, such as black and grey, are added.

Shoes

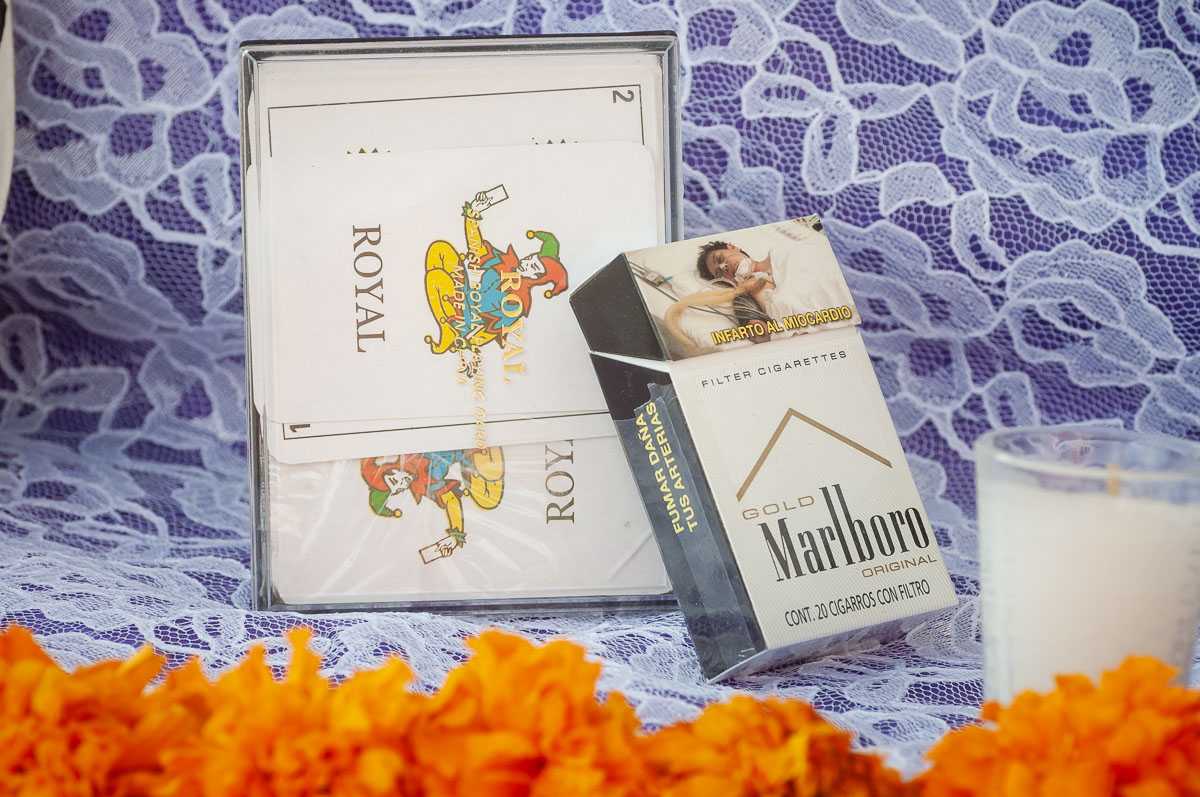

Footballs, playing cards, cigarettes, toys, books or anything that was significant to the dead might be placed on the altar, including professional items from the deceased’s life, such as these field tools.

Soap and Water

The soap, a basin of water and the towel help the spirits of the dead bathe and keep clean while they are back on earth. Pitchers of water are also left so the spirits can quench their thirst after a presumably long journey back home from the afterlife.

Mirrors

An altar might have a mirror to help the dead check their appearance after washing and freshening up.

Petates

These woven mats made from tule reeds were once commonly used as a mat for sleeping. On the Day of the Dead, a petate is sometimes put out so the spirits have a place to sleep.

Plates of Food

Leaving out a plate of favorite food is one of the many personal ways of remembering the dead.

Alcohol

The dead’s favorite drink is laid out: a bottle of tequila or beer, or perhaps a cup of pulque. Non-alcoholic drinks are also offered such as atole, which is a hot drink made from masa and water.

Fruits and Vegetables

Also left out are fruits and vegetables, along with plates of rice, beans, mole (a type of sauce) or other traditional foods.

Coronas

Coronas de flores, or crowns of flowers, are often placed on graves after burial, with new coronas being purchased each Day of the Dead to replace the old ones.

Metates and Molcajetes

The metate, made from volcanic rock, has been used for centuries to grind corn into masa for tortillas, sopes, huaraches, and dozens of other variations. Today, however, machines are mostly used and masa can be bought at any tortilla shop.

A molcajete (mortar) and tejolote (pestle) are still commonly found in home and commercial kitchens in Mexico. They’re used to grind spices, make salsas and guacamole, and are even heated up and used as serving bowls for dishes called molcajetes.

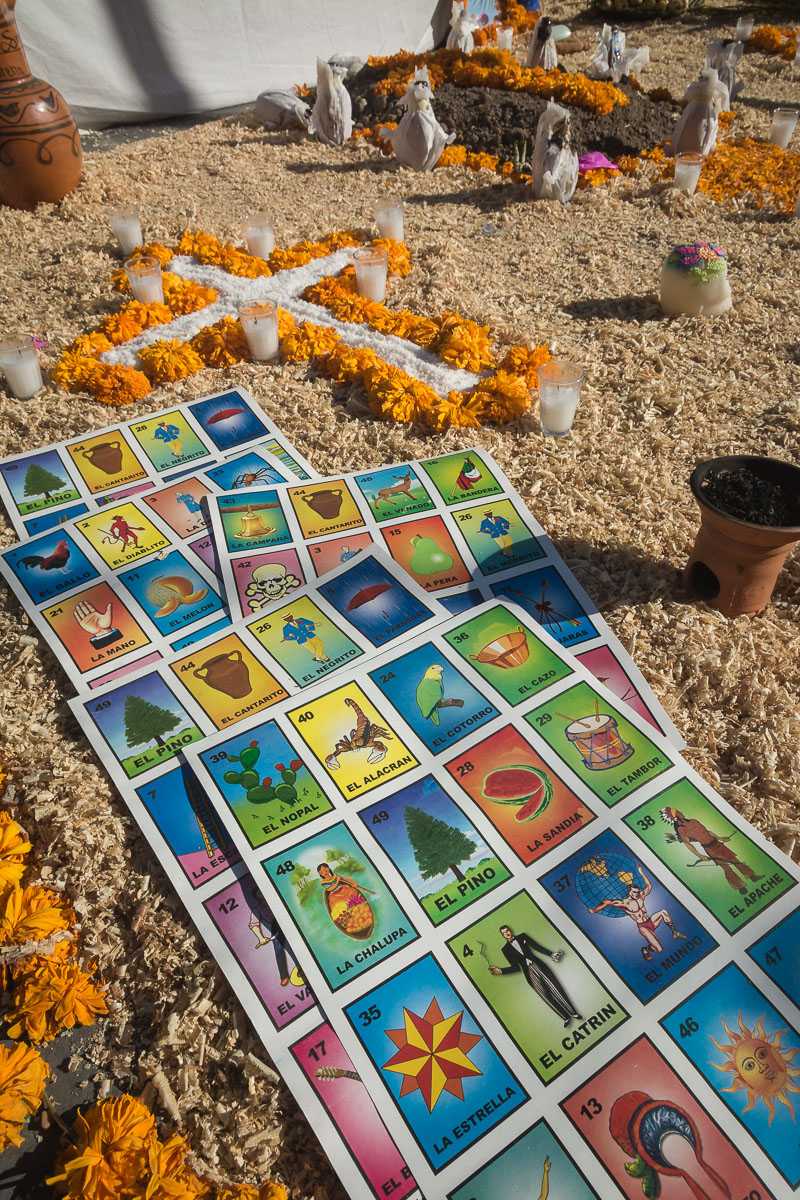

La Lotería Mexicana

This popular children’s game is played during parties and is a part of everyone’s childhood, finding its way into jokes and, in 2018, into Ajijic’s New Year’s parade. It’s not commonly left on a Day of the Dead altar, but can be found on occasion.

Traditional Dolls

This popular children’s game is played during parties and is a part of everyone’s childhood, finding its way into jokes and, in 2018, into Ajijic’s New Year’s parade. It’s not commonly left on a Day of the Dead altar, but can be found on occasion.