I Quit My Job & Moved to Mexico with an Ex-Member of the Weather Underground… And 7 Years Later I’d Never Move Back to the United States

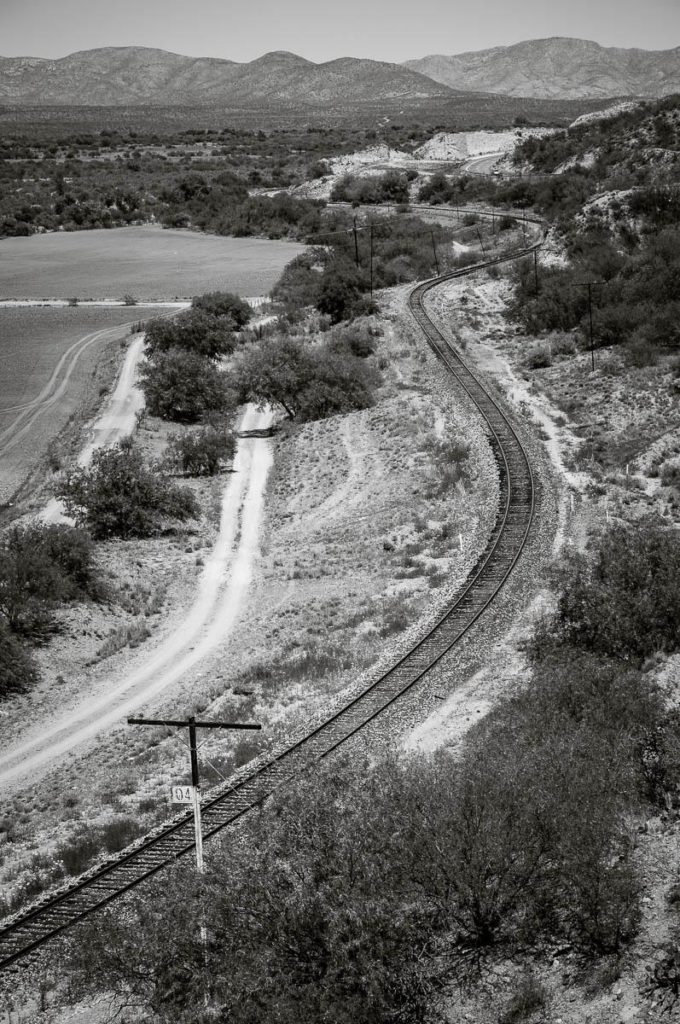

2,200 Miles, 2 Breakdowns & 14 Days Driving in a Non-Air Conditioned Suzuki Deathtrap

By the time our 1994 fire engine red Suzuki Samurai — which my friend described as “basically like driving a covered motorcycle” — bounced across the Mexican border, we had already broken down once for three days in Arizona. Finally dipping our toes into Mexico after six months of anticipating our trip, then being forced to suffer three more days among the Olive Garden-encrusted parking lots of Phoenix, felt exhilarating.

I was 26, and obviously stupid, as the year before I had decided to quit my job and move 1,300 miles south to a village in the central mountains of Mexico.

What, me worry?

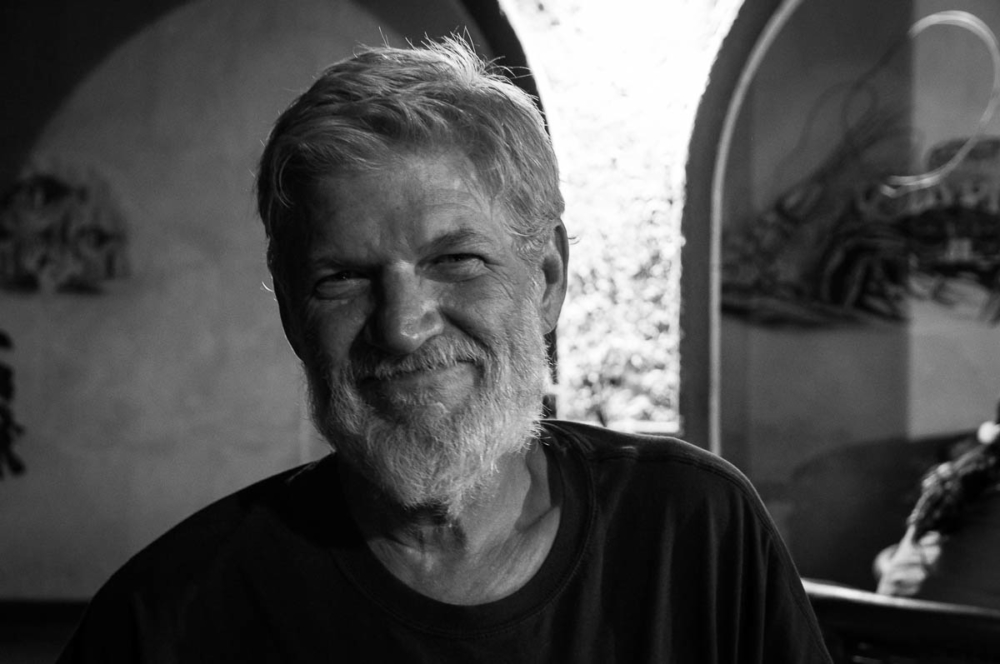

My friend was considerably older than me, the same age as my mother. Our friendship was the product of hundreds of hours of playing guitar in our living rooms in Denver, multiplied by not one too many skunky Colorado joints, which usually gave the notes extra twang and made ’em sing.

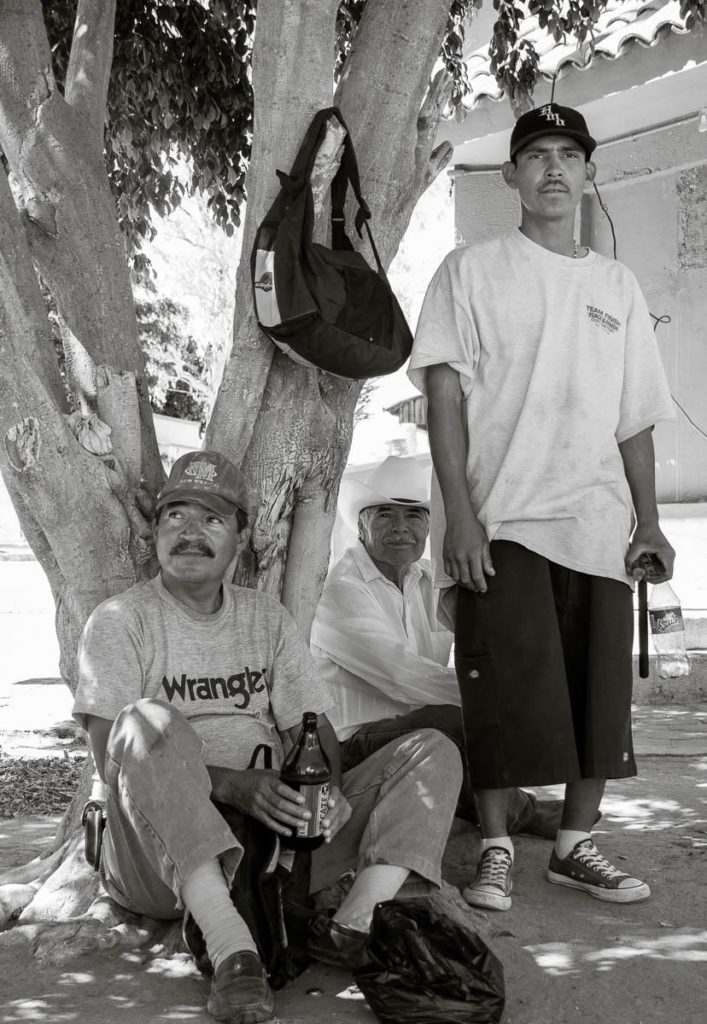

Since the mid-2000s Bruce had spent years moving back and forth between Denver and Jalisco, Mexico, living on the north shore of Lake Chapala, the country’s largest lake. He found it easy to get lost in life in Mexico, moving anonymously with its down-to-earth, sociable people. Here he felt like he could live freer, more openly and without reproach, away from his early Oklahoma background, and out of the confines of American bureaucracy and institutional violence.

Bruce, you see, was a former member of the Weather Underground replete with a closed FBI file. And I moved to Mexico with him. While Sarah Palin was slurring incoherences about Obama pallin’ around with terrorists, I actually was!

For my fellow millennials, no, the Weather Underground was not an avante-garde experimental rock group headed by Lou Reed in 60s. (You’re thinking of the Velvet Underground.) The Weather Underground is considered by history to be America’s first domestic terrorist organization, founded in 1968 by members of Students for a Democratic Society. Their goal? To create a clandestine vehicle to overthrow the US government for crimes committed against the North Vietnamese people, as well as minorities and the poor back home in the United States.

This moral prerogative forced the group into the headlines and set it on an often violent collision course with government agencies until the mid-70s, by which time the group had been disbanded, its members being behind bars or living under aliases in anonymity.

One of its leaders, Bill Ayers, went on to become a distinguished professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, living the rest of his post-Weatherman days in relative obscurity. Until Sarah Palin “revealed” in the 2008 election campaign that Barack Obama had once met Ayers, already public knowledge for many years.

The Weathermen, along with the Black Panthers, had been targets of the government’s COINTELPRO operation, which used illegal, covert techniques to put an end to movements such as the Weather Underground. One of the other primary targets of COINTELPRO’s black-ops during the late 60s was Martin Luther King, including other civil rights and anti-war organizers.

Not only had Bruce been a 17-year-old Weatherman in the late 60s, he was also a (white) Black Panther. Though Bruce was polite and usually quiet, he could be a talker and had a way of telling stories, making them come alive the way only a manic depressive can.

Over the years he had told me a number of them: When the Weathermen broke Timothy Leary out of the California Men’s Colony in 1970, they used their network to smuggle him out of the country to Argentina. It had come down to Bruce and another Weathermen to drive Leary east of Denver to the coast. Another Weatherman was selected to be the driver and Bruce was relieved. On one occasion, Bruce was at the local Blank Panther headquarters when Jane Fonda popped in. Another time he contributed stolen dynamite to blow up a Denver draft office with a VW Bug.

And the tales of his later life south of the border were alluring, too: houses for rent for $100. All-night, Mezcal-infested fiestas in the plaza going on for a week and a half. An ex-NFL player on the lam for decades after a botched robbery-gone-murder, who sold drugs out of his home to the local ex-pats. An end-of-times couple waiting out 2012 in the land of the Maya (post-2012, they’ve since graduated to Alex Jones).

And then, not lastly, there was the freedom you seemed to have to do as you like and be as you are in a country that’s often said by its own people to be closer to the United States than it is to God.

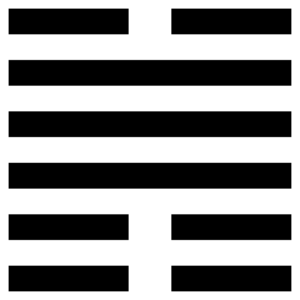

A lake on the mountain:

The image of influence.

Thus the superior man encourages people to approach him.

By his readiness to receive them.

A mountain with a lake on its summit is stimulated by the moisture from the lake. It has this advantage because its summit does not jut out as a peak but is sunken. The image counsels that the mind should be kept humble and free, so that it may remain receptive to good advice.

Plus the kicker was that Lake Chapala has a two-season climate, rainy in the summer and dry the rest of the year, with near-perfect year-round temperatures. One of the world’s beautiful natural paradises, a lake somewhat paradoxically on top of a mountain. In the ancient Chinese book of the I Ching, it was number 31: Influence (Wooing), the hexagram for a lake on a mountain. Between nature and culture, it was a photographer’s paradise. And in 2010 I was less than a year into my photography career.

I was down. I was wooed. If Bruce couldn’t drive Timothy Leary out of the country, he could drive me out instead.

I wasn’t on the run from anything and I hadn’t killed anyone in a botched robbery. I didn’t even like football. But I had spent seven not-so-short years as an editorial assistant at the city desk in The Denver Post newsroom. Seven years which had started the week the United States invaded Iraq in 2003 and ended a year and a half into Obama’s first term, just after the end of the Great Recession. I was ready for a change.

It was 18 months after the worst economic disaster since the Great Depression. I had a safe, secure job and, at the last minute, the opportunity for advancement at the newspaper’s growing online department. As I said, I was stupid. But you would have to be in order to end up doing the greatest thing you’ve ever done with your life.

The second time we broke down, we were in the Sonoran Desert. The morning was sunny, fair, 80 degrees. Your average pre-afternoon, candle-melting morning in Mexico. And we were motoring along at top speed, about 55 MPH.

The Suzuki Samurai is famously unsafe. Suzuki stopped making it after a damning Consumer Reports review said that it rolled over easily when making sharp turns.

You know, like when a driver swerves on the road to avoid stuff.

In Mexico, stuff on the road that you might want to swerve to avoid includes: steer, horses, and other large livestock, either escaped or left to roam freely along the highway (possibly at night).

Bruce’s Suzuki Samurai, vintage 1994, had decided to take things one step further. The thing had a wooden fence post for a front bumper. There were no shocks. You couldn’t turn the windshield wipers and headlights on at the same time or the battery would drain (even while driving).

It had no air-conditioning, so you had to drive with the windows down or the cabin would heat up and turn into a Greek bath. After a few days of driving, you’d wake up in the morning with black dirt stuffed deep in your dried-out nose.

There was no radio. Six- to eight-hour drives were done in complete silence or in loud conversation since the windows were always down, so all we could hear was the steady wind plus the Suzuki’s soft plastic roof flip-flapping above the humble grind of its two-stroke engine, as we chugged along the wavy asphalts of the Mexican federal highway system.

At least we didn’t have to listen to any Tom Jones or any kind of weird shit like that. Not that either of us was into that. The trip so far had given us (or me, at least) plenty of time to stare out the window at the dry desert landscape and wonder what the hell I had done… quitting my 7-year pensioned job and moving to Mexico… as we scooted for hours south into the ever-tightening vortex of Highway 15.

Consumer Reports would have given Bruce’s Suzuki a big “F.”

Before leaving Denver I had bought a small, five-foot trailer and Bruce had found a way to hook it to the back of the Suzuki. And before leaving we’d stuffed it and the car with pretty much all of our belongings: four guitars, two amplifiers, clothes, pots and pans, computers and monitors, camera gear, plus an image of the Virgin Mary, for protection.

At the end of the day, all of this had to be unpacked into the hotel room and scientifically repacked into the Suzuki and its trailer the following morning before starting the day’s drive. Whenever possible, we tried to stay in one of the “love motels” along the highway. Their anonymous, drive-in garages meant we didn’t have to lug everyone in and out after each leg of the trip.

So while motoring along at 55 MPH, it probably shouldn’t have come as any surprise when the car suddenly exploded. The whole thing began to shudder and shake as Bruce wrestled to control it, and we pulled off into the center median.

A minute later we were under the car. Semi trucks, which use Highway 15 to transport goods up and down the country, barreled by at 70 MPH as we inspected the undercarriage to figure out what happened.

The brake line was shorn off and fluid was pumping out. Seemed like it might be the problem. But Bruce had noticed something even more terrible.

“Dude, the driveshaft is gone.” Gone? Where’d it go?

The damn driveshaft had fallen out of the car. It had flown off like a flecha into the great Mexican ether, never to be seen by another gringo again.

Major Car Problems in the Sonoran Desert

Now, I’m no car expert. I haven’t owned one in twelve years. But I do know that the driveshaft is an important, perhaps vital, part that makes a car vroom-vroom. Without it, one cannot go-go. We tried, though. Bruce threw the car into four-wheel-drive and we hobbled down the freeway — at 10 MPH for about a minute. Then we pulled back to the side of the road and began to assess our situation.

Location: the Sonoran desert (Mexico’s hottest desert) somewhere south of Hermosillo and north of Ciudad Obregon. Supplies: 1/3 of a bottle of water and no food, a lot of guitars and two amplifiers, but no place to plug them in. No cell phone. And no number to call. (After all, this was 2010. The first-generation iPhone had been out less than three years. We couldn’t look anything up, anyway.)

The semi-trucks were continuing to jet past us on their way to delivering Bimbo-brand bread to the four corners of Mexico.

Just then, an ice truck approached from the opposite direction and pulled off to the other side of the road. This was probably our best chance. I mean, sometimes in Mexico, you can’t even find ice in a restaurant.

I, being the guy who knew at least a little Spanish, was the one who was volunteered to run over to the strangers in the ice truck to ask for help.

It was my second day in Mexico and I was about to put my Rosetta Stone-Spanish to the test.

Two young guys were at the back of the truck and one was inside adjusting something. Its cool interior looked inviting and refreshing. I thought about locking myself inside and heading north back to the border with them.

Instead, I tried to explain. “Hola! Necesitamos un…” The word for “tow truck” wasn’t a part of my vocabulary, yet. But what they say about learning a language in context is true: doing it contextually through experience helps you remember stuff.

“Um….” I made the international hand gesture for a tow truck.

“Grúa!” one of them volunteered.

What proceeded was five minutes of calling various numbers, exchanging phones back and forth, trying to describe our location, until, finally, it seemed, my new friends indicated that someone was on the way. To wherever the hell we were located on Highway 15 in the Sonora Desert.

I awkwardly offered them $200 pesos, about $10 USD, which they waved off, and I ran back to the other side of the freeway.

“It’s on the way,” I told Bruce.

“How long did they say?”

“No idea.”

We took a gulp from our third-full bottle of water.

Rescued by a Green Angel

The Green Angel arrived four hours later. Bruce was watching his truck approach from the south.

“He’s here!”

I was off the side of the road, having spent an hour or two under the cool shade of the nearby freeway overpass. Our water bottle was near empty. I raced up the ravine and to the freeway to meet our savior. It was 3:30 and the afternoon sun was nearing its hottest.

There he was: our Green Angel. He had a buzzcut and the bright overhead light was sending reflections off his aviator sunglasses. He projected the confidence and outward self-assuredness of a man who would be able to get anyone out of the Sonoran Dessert. Or at least make them feel better about being stranded there. He asked us what the problem was and then he began to get to work.

The Green Angels wander the toll roads and federal highways in Mexico, offering assistance to stranded travelers since being formed in 1960. Need travel advice? Call ’em up. Broken down and need something fixed? They can help. Need a tow? Yes. We needed a tow, we explained to our Green Angel in our broken Spanish. But he had arrived in a regular truck. Not a tow truck.

Our Green Angel explained something which must have been several sentences of Spanish put together but sounded to us like a single uninterrupted word, to which we nodded our heads and pretended to understand with real enthusiasm. 10 minutes later I was in the cool cab of his truck listening to the latest banda hits. The Suzuki was tied up to the back of the Green Angel’s truck.

He had used a thick rope to tie it to the wooden fence post bumper on the Suzuki. Bruce was now behind us in the Suzuki steering.

We drove for about 45 minutes before arriving in the middle of nowhere and when we pulled off to the side of the road again, Bruce was still behind us, attached firmly to the Green Angel’s truck with the rope.

The Green Angel said something in Spanish as we stood and we waited on the side of the ride in the hot desert sun.

“What’s going on?” Bruce asked me.

“I don’t know.”

How to Be Confused in Spanish

Someone else was coming. So we waited. And waited. And probably waited a few minutes more. Standing out in mid-afternoon sun in the Sonoran Desert, it felt like forever. But it was better than sitting inside the damned Suzuki.

The Green Angel looked down the highway and scanned the horizon. “Ya viene.” There was a tiny dot on the road and it was coming towards us. It slowly graduated from dot to thing and got larger, until Bruce and I could tell what it was: a tow truck.

As it turns out, the tow truck was only allowed to travel a certain distance and the Green Angel had needed to drive us to meet him. From here, the tow truck would drive us to Ciudad Obregón, the nearest populated area. Of course, we only figured all this out later once we got dropped off there.

I could see Bruce getting nervous. How much was this going to cost? Bruce survived, barely, on Social Security, less than $1,000 a month. It was one of the reasons he liked to live in Mexico — because he could, actually, live here.

The Suzuki and its trailer almost didn’t fit on the back of the tow truck’s platform. Half of the wheels didn’t make it and the back of the trailer extended beyond the end of the tow truck. But we were in the cab and heading to Ciudad Obregón.

When we got to the city, he unloaded the Suzuki deathtrap into the nearest Wal-Mart parking lot. It was time to pay. We held our breath.

“¿Cuánto cuesta?” we asked the driver, who sported a permanent grin and looked around 65.

He waved his hand and brushed our question aside. “It’s free.”

We immediately tipped him 200 pesos and hobbled to the nearest hotel by the miracle of four-wheel drive, and a little help from the image of the Virgin Mary that had been tucked into the back of our Suzuki Samurai deathtrap.

I’m still living in Mexico, seven years on. Bruce died in 2013 after a decades-long battle fighting incredulous medicaid doctors about his undiagnosable case of chronic gastrointestinal illness. Using Google, I recently decided to look up his symptoms. I randomly typed in the two best words I could think of:

vomiting cyclical

The first results that came back described his symptoms and how to relieve them (hot water) almost perfectly.

Bruce almost certainly had one of two syndromes, none of which were officially recognized until after 2010: cyclic vomiting syndrome or cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (basically an allergy to marijuana ingestion). It’s something he developed in his 20s and lasted until his death at 60. His body just wore out because of it. Today, he might be able to get a diagnosis, in spite of his medicaid status. But only a few years before he died, he couldn’t get a doctor to take him seriously.

So I’m here now, in Mexico. Seven years. And if I had the choice, I’d never go back to the United States again, especially with How Things Are Now. But I know one thing, if I ever do return…

I’m not driving there.

Photos about moving to Mexico continue below